Warning: this page refers to an old version of SFML. Click here to switch to the latest version.

Threads

What is a thread?

Most of you should already know what a thread is, however here is a little explanation for those who are really new to this concept.

A thread is basically a sequence of instructions that run in parallel to other threads. Every program is made of at least one thread: the main one, which

runs your main() function. Programs that only use the main thread are single-threaded, if you add one or more threads they become

multi-threaded.

So, in short, threads are a way to do multiple things at the same time. This can be useful, for example, to display an animation and reacting to user input while loading images or sounds. Threads are also widely used in network programming, to wait for data to be received while continuing to update and draw the application.

SFML threads or std::thread?

In its newest version (2011), the C++ standard library provides a set of classes for threading. At the time SFML was written, the C++11 standard was not written and there was no standard way of creating threads. When SFML 2.0 was released, there were still a lot of compilers that didn't support this new standard.

If you work with compilers that support the new standard and its <thread> header, forget about the SFML thread classes and use it instead -- it will

be much better. But if you work with a pre-2011 compiler, or plan to distribute your code and want it to be fully portable, the SFML threading

classes are a good solution.

Creating a thread with SFML

Enough talk, let's see some code. The class that makes it possible to create threads in SFML is sf::Thread, and here is what it

looks like in action:

#include <SFML/System.hpp>

#include <iostream>

void func()

{

// this function is started when thread.launch() is called

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

std::cout << "I'm thread number one" << std::endl;

}

int main()

{

// create a thread with func() as entry point

sf::Thread thread(&func);

// run it

thread.launch();

// the main thread continues to run...

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

std::cout << "I'm the main thread" << std::endl;

return 0;

}

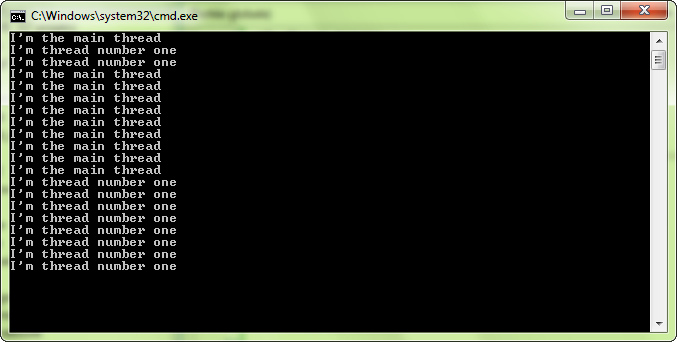

In this code, both main and func run in parallel after thread.launch() has been called. The result is that

text from both functions should be mixed in the console.

The entry point of the thread, ie. the function that will be run when the thread is started, must be passed to the constructor of sf::Thread.

sf::Thread tries to be flexible and accept a wide variety of entry points: non-member or member functions, with or without

arguments, functors, etc. The example above shows how to use a non-member function, here are a few other examples.

- Non-member function with one argument:

void func(int x)

{

}

sf::Thread thread(&func, 5);

- Member function:

class MyClass

{

public:

void func()

{

}

};

MyClass object;

sf::Thread thread(&MyClass::func, &object);

- Functor (function-object):

struct MyFunctor

{

void operator()()

{

}

};

sf::Thread thread(MyFunctor());

The last example, which uses functors, is the most powerful one since it can accept any type of functor and therefore makes sf::Thread compatible with many types of functions that are not directly supported. This feature is especially interesting with C++11 lambdas or

std::bind.

// with lambdas

sf::Thread thread([](){

std::cout << "I am in thread!" << std::endl;

});

// with std::bind

void func(std::string, int, double)

{

}

sf::Thread thread(std::bind(&func, "hello", 24, 0.5));

If you want to use a sf::Thread inside a class, don't forget that it doesn't have a default constructor. Therefore, you have to

initialize it directly in the constructor's initialization list:

class ClassWithThread

{

public:

ClassWithThread()

: m_thread(&ClassWithThread::f, this)

{

}

private:

void f()

{

...

}

sf::Thread m_thread;

};

If you really need to construct your sf::Thread instance after the construction of the owner object, you can also

delay its construction by dynamically allocating it on the heap.

Starting threads

Once you've created a sf::Thread instance, you must start it with the launch function.

sf::Thread thread(&func);

thread.launch();

launch calls the function that you passed to the constructor in a new thread, and returns immediately so that the calling thread can

continue to run.

Stopping threads

A thread automatically stops when its entry point function returns. If you want to wait for a thread to finish from another thread, you can call its

wait function.

sf::Thread thread(&func);

// start the thread

thread.launch();

...

// block execution until the thread is finished

thread.wait();

The wait function is also implicitly called by the destructor of sf::Thread, so that a thread cannot remain alive

(and out of control) after its owner sf::Thread instance is destroyed. Keep this in mind when you manage your threads (see the last

section of this tutorial).

Pausing threads

There's no function in sf::Thread that allows another thread to pause it, the only way to pause a thread is to do it from the

code that it runs. In other words, you can only pause the current thread. To do so, you can call the sf::sleep function:

void func()

{

...

sf::sleep(sf::milliseconds(10));

...

}

sf::sleep has one argument, which is the time to sleep. This duration can be given with any unit/precision, as seen in the

time tutorial.

Note that you can make any thread sleep with this function, even the main one.

sf::sleep is the most efficient way to pause a thread: as long as the thread sleeps, it requires zero CPU. Pauses based on active waiting,

like empty while loops, would consume 100% CPU just to do... nothing. However, keep in mind that the sleep duration is just a hint,

depending on the OS it will be more or less accurate. So don't rely on it for very precise timing.

Protecting shared data

All the threads in a program share the same memory, they have access to all variables in the scope they are in. It is very convenient but also dangerous: since threads run in parallel, it means that a variable or function might be used concurrently from several threads at the same time. If the operation is not thread-safe, it can lead to undefined behavior (ie. it might crash or corrupt data).

Several programming tools exist to help you protect shared data and make your code thread-safe, these are called synchronization primitives. Common ones are mutexes, semaphores, condition variables and spin locks. They are all variants of the same concept: they protect a piece of code by allowing only certain threads to access it while blocking the others.

The most basic (and used) primitive is the mutex. Mutex stands for "MUTual EXclusion": it ensures that only a single thread is able to run the code that it guards. Let's see how they can bring some order to the example above:

#include <SFML/System.hpp>

#include <iostream>

sf::Mutex mutex;

void func()

{

mutex.lock();

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

std::cout << "I'm thread number one" << std::endl;

mutex.unlock();

}

int main()

{

sf::Thread thread(&func);

thread.launch();

mutex.lock();

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

std::cout << "I'm the main thread" << std::endl;

mutex.unlock();

return 0;

}

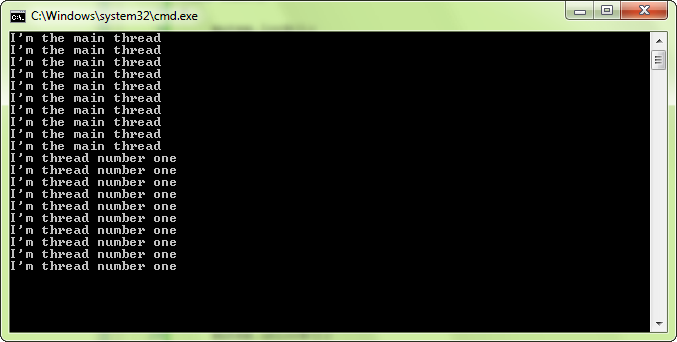

This code uses a shared resource (std::cout), and as we've seen it produces unwanted results -- everything is mixed in the console.

To make sure that complete lines are properly printed instead of being randomly mixed, we protect the corresponding region of the code

with a mutex.

The first thread that reaches its mutex.lock() line succeeds to lock the mutex, directly gains access to the code that follows and prints

its text. When the other thread reaches its mutex.lock() line, the mutex is already locked and thus the thread is put to sleep

(like sf::sleep, no CPU time is consumed by the sleeping thread). When the first thread finally unlocks the mutex, the second thread

is awoken and is allowed to lock the mutex and print its text block as well. This leads to the lines of text appearing sequentially in the console instead of being

mixed.

Mutexes are not the only primitive that you can use to protect your shared variables, but it should be enough for most cases. However, if your application does complicated things with threads, and you feel like it is not enough, don't hesitate to look for a true threading library, with more features.

Protecting mutexes

Don't worry: mutexes are already thread-safe, there's no need to protect them. But they are not exception-safe! What happens if an exception is thrown while a mutex is locked? It never gets a chance to be unlocked and remains locked forever. All threads that try to lock it in the future will block forever, and in some cases, your whole application could freeze. Pretty bad result.

To make sure that mutexes are always unlocked in an environment where exceptions can be thrown, SFML provides an RAII class to wrap

them: sf::Lock. It locks a mutex in its constructor, and unlocks it in its destructor.

Simple and efficient.

sf::Mutex mutex;

void func()

{

sf::Lock lock(mutex); // mutex.lock()

functionThatMightThrowAnException(); // mutex.unlock() if this function throws

} // mutex.unlock()

Note that sf::Lock can also be useful in a function that has multiple return statements.

sf::Mutex mutex;

bool func()

{

sf::Lock lock(mutex); // mutex.lock()

if (!image1.loadFromFile("..."))

return false; // mutex.unlock()

if (!image2.loadFromFile("..."))

return false; // mutex.unlock()

if (!image3.loadFromFile("..."))

return false; // mutex.unlock()

return true;

} // mutex.unlock()Common mistakes

One thing that is often overlooked by programmers is that a thread cannot live without its corresponding sf::Thread instance.

The following code is often seen on the forums:

void startThread()

{

sf::Thread thread(&funcToRunInThread);

thread.launch();

}

int main()

{

startThread();

// ...

return 0;

}

Programers who write this kind of code expect the startThread() function to start a thread that will live on its own and be destroyed

when the threaded function ends. This is not what happens. The threaded function appears to block the main thread, as if the thread wasn't working.

What is the cause of this? The sf::Thread instance is local to the startThread() function and is therefore immediately destroyed,

when the function returns. The destructor of sf::Thread is invoked, which calls wait() as we've learned above, and

the result is that the main thread blocks and waits for the threaded function to be finished instead of continuing to run in parallel.

So don't forget: You must manage your sf::Thread instance so that it lives as long as the threaded function is supposed to run.